Give Me Shelter: A Strong Towns conversation w/Chuck Marohn

Give Me Shelter: Solving Lancaster’s Housing Crisis w/ Local Development

A Strong Towns Conversation with Chuck Marohn

West Art | Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025

Samantha Gray (Coalition for Sustainable Housing) – Opening Remarks

Well, thank you all for coming. My name is Samantha Gray, and I am your host for this evening. I am the director of the Coalition for Sustainable Housing, and I'm really excited to welcome everyone here. It's great to see such a mix of neighbors and leaders and partners to talk about how we can build stronger, more connected places in Lancaster.

We know that Lancaster County has always seen itself as a place of rolling farmland, small towns and close-knit communities, and for good reason. Our agricultural land is world class. Our downtowns are vibrant, and our sense of place runs deep. But we also know that the landscape is changing. Fields that once seemed untouchable are now subdivisions. The cost of housing has outpaced what most working families can afford, and for many, finding a place to call home feels harder than it should.

We say that we value small towns, that we value family, yet as a county, we're still trying to figure out how to grow in ways that truly reflect those values. And that's why we're here tonight. We want to talk honestly about what it means to build a housing-ready Lancaster. Strong Towns calls this a housing-ready ecosystem, one that's built on clarity, connection, culture and capital. It's about creating the conditions for local builders, developers and communities to do what they already do best: build incrementally, thoughtfully and in ways that strengthen the places that we love.

Before we get started, I'd like to get a sense of who's in the room. So, how many folks are here from the city and consider yourself city folk? Nice. How many consider yourself (from) the counties, boroughs or townships? Nice. What about municipal leaders here—elected officials, staff, planning commission members? Okay. Developers, realtors? We've got some developers and realtors in the house. Nice. What about banking, finance? Anybody in banking or finance? What about those working in nonprofit housing or social services? We should have a bunch of those too, nice. And finally, the most important question: how many of you are here because you care about making sure everyone who wants to call Lancaster home can do that in ways that are affordable, sustainable, and within reach?

So that's the spirit of tonight. We really want to encourage conversation, curiosity and connection. So, please, it's fine to get up and get your food and get your drink. We want it to be easy and relaxed for you to be able to think and share together.

We want to give first a big shout out to West Art for welcoming us here to this place. If you’re not familiar, the restrooms are downstairs. There's also an elevator for folks that might need that. And if you haven't experienced it yet, they have a cash bar as well with everything from kombucha to beer to mixed drinks, so you should be able to find something you like out there.

We also want to thank our sponsors who helped make tonight's event possible: the Coalition for Sustainable Housing, Strong Towns Lancaster, the Lancaster County Community Foundation, the Lancaster City Alliance, Larkstone and Kegel’s Produce. I also want to recognize the team behind the scenes, the often invisible hands that make all of this happen. I want to thank Christian Hinojosa, Tim Stuhldreher, Sarah Etter. We also have Lea Zikmund, Nick Dennis, Matt Johnson, Tom Becker, Lauren Casale and Evan Young.

OK, so here's how the flow tonight will go. I think you’re aware of this, but just so you know. We're going to start with Chuck Marohn, founder of Strong Towns. Then we're going to move into a panel discussion with some local leaders, and then after that, we'll open it up for some audience questions. Just as a little forewarning, because we have wired mics, if you have questions, we're going to have one microphone up here at the front, so you can come up front and ask questions during that time. After that, I will turn it over to Nick Dennis, who will close for us, and then you'll have some time to mix and mingle.

So that’s how our evening will go. Now I would like to introduce Tom Becker from the Row House and Strong Towns Lancaster to introduce our guest for the evening.

Tom Becker (Row House) – Introduction of Chuck Marohn

Thanks for coming out. Thank you so much for joining us for the great conversation we’re about to have. I was looking through the history of Chuck Marohn's visits to Lancaster. It goes back to January 2013 when he spoke at a Lancaster County Planning Commission forum. He called the development patterns that we find in America a sort of Ponzi scheme. I think that got people’s attention. Then in 2019 he was in York —I believe I may have seen him at that time—and he came to the Trust Performing Arts Center in ‘19. Actually no, we did a Strong Towns event without him. One of his associates, Bo Wright, gave a talk in that one. In 2023 he came to the Hourglass Foundation to do one of their community forums. It’s great to have him back.

When you introduce someone, I enjoy mentioning their accomplishments, but also saying something about their character. So, really quick. His accomplishments are all over the place—traffic engineer training and all the kudos that go along with that. But also, after that, he's written books about transportation and housing through his platform and through the group he started called Strong Towns, and that's where you’re going to learn from tonight. He's the founder of Strong Towns, and it's an incrementally growing movement.

There are so many other accolades we could give Chuck Marohn. But I want to say something quick about his character. I was listening to a podcast that he re-published on his podcast. He was on with some young adults, hipsters you might say, people like myself, who might be considered bike advocates for people who are into walkability. He was invited on to this podcast, Bike Talk, because of some tweeting he had been doing, which suggested that we ought to have more empathy toward car drivers. This got the bike snobs' attention, and me, too, and they invited him on, almost like maybe in the lion’s den, something adversarial. But what Chuck did in that moment has never left me. I've studied it, actually.

He did four things when he had this opportunity to maybe do a slam dunk on some people who virtually (unclear) people with cars. Their concerns are that cars are too dangerous, they kill people unnecessarily. There are all these concerns, right? I think the first thing he did was to aspire with them, he met them in this common ground, which is we all, of course, want safe streets. And we all want to stay away from shaming people who maybe have a different view than urbanists have. Right off the bat, he made common ground with them to aspire for something greater, even in the rhetoric. The second thing he did was he empathized with these people who were hosting. He said, "Yeah, cars are very dangerous, (inaudible) the way we built our environment. Yeah, it's a big problem." So he empathized with their concern. And then thirdly he offered a suggestion: The problem is not necessarily the size of the automobile, but it is the built environment. He got into that with them and of course they could agree with that. And I think in all of that, the fourth thing overall he did is, he explained. And what he was trying to do in that moment is to not shame them for maybe something they were trying to espouse but (inaudible). He didn't take that approach. (inaudible) He showed them a way toward leading them to make common ground with them. And I know that his rhetoric was effective, because as he explained all this, they asked him questions. ‘So Chuck, what do we do …?” And they started to think in other ways because of his graciousness.

That's the sort of thing I've seen in Chuck, publicly and privately. It’s the sort of thing that speaks to his character. … So thank you Chuck for coming out, thank you guys for coming out tonight, and let's not be reserved. Let's just let loose here and let’s give him a warm and robust Lancaster welcome.

Chuck Marohn (Strong Towns) – Keynote Presentation

That was very kind. I will try to be worthy of that. I go home to my wife and my two kids—my daughters are now in college, so not in the house anymore—but they always say, "Dad, you're not that cool."

Thank you. It is very nice to be back. This is a vibe that I love, right? I spoke at a conference today, and it was really great—a lot of regional commissioners and important people, but people who are earnestly trying to get things done. That was a great vibe too. They were very into it. They wanted to learn, they wanted to change, they were very excited. I got a quasi standing ovation at the end. There were a handful of people in the room, at least six people. “Dad, you’re not that cool.”

But this is amazing, so I thank you for taking a Thursday night out to come here and chat about this stuff.

The History of Housing Finance

I want to talk about, to set the stage for the conversation we’re going to have later today. I want to put us all in a frame of mind about the way that housing used to be financed, because this is the big driver of the angst and the tension that we have today. For many of us, it's very opaque. It's not something that we deal with regularly.

If you were going to, say in the 1920s—so, 100 years ago—buy a house and you were going to get a mortgage for that house, you were going to get that mortgage at a local bank. That local bank was going to be a very, very conservative institution. I don't mean conservative politically. I mean they were extremely risk averse. So they were going to require you to have a 50% down payment, and then they were going to finance that loan for you over a two, a three, four, five year period of time with a balloon payment at the end. You were going to make interest-only payments, and then at the end you would either pay it off, or more likely, roll it over into a new loan.

This was a very common way of financing housing, not just here in North America, but really all over the world, going back a long, long, long period of time. Let me emphasize again: 50% down payment. Because for us, that seems insane today. I hope by the end tonight, you realize that we live in an insane world, not them.

Why would you want such a down payment? Because the bank obviously wanted to have the homeowner to have a lot of skin in the game, right? A lot of buffer. If things didn't work out and they had to repossess the home, they wanted to be able to make good on the money that they had lent out. Because whose money was that? That was the depositors' money. And where did that money come from? In 1920s America, it came from the people who were living in the community. So in a sense, a covenant. A steward of your money, they wanted when they lent it out to have a lot of backstop, a lot of skin in the game.

The Great Depression and Federal Intervention

During the Great Depression, this system broke down. It broke down for a number of reasons. The 1920s were kind of a crazy distortion period of time where some crazy speculative lending happened. But when it comes to the housing market, there was a mechanism involved here in the drama of the run-up and the rundown that had a big effect.

Let's say that you had gotten a mortgage and the bank had said, "Here's what your house is worth and now we’ll lend you 50% of that.” Now your three year, four year, five year balloon payment comes due, and you go in to refinance and the bank says, "Well, it's the Great Depression. Your house value has dropped. We will still lend you 50% of that value. No problem. You've been good for it, you've made your payments on time, you've got a job, we believe you'll continue to make payments. It's all good, but we can only lend you 50% of what your house is worth."

The problem is that now there's a gap between the money you owe in this rollover and the money that they will actually lend you, and you need to come up with that difference in cash. During the Great Depression, when the economy is melting down, there's 25% unemployment, there's massive dislocation, a lot of people couldn't do this. And what happened was, through no fault of their own—like I said, they were making the payments, everything was fine, they would continue to make the payments gladly—but they would lose their house. They would get kicked out of their property.

What happens when a house is foreclosed on? What does the bank do with it? Does the bank keep it in their portfolio? Throw a party? No, what they do is they sell it. They sell it. There's a lot of equity, right? Do they try to get the highest price? No, what are they trying to do? Just recoup their losses. So what happens to a market that's in decline when you add more supply to it? What happens to prices? They go down. What happens then to the next person who comes in and has to refinance their balloon payment? There's an even bigger gap between what they owe and what their house is worth, because housing prices are going down.

This is called a deflationary spiral. In the beginning of the 1930s, this is what the Great Depression was. It was a deflationary spiral that was catching more and more and more people who, by all accounts, were paying their debts, making good on things, trying to do everything they could, but they were getting caught in this deflationary spiral.

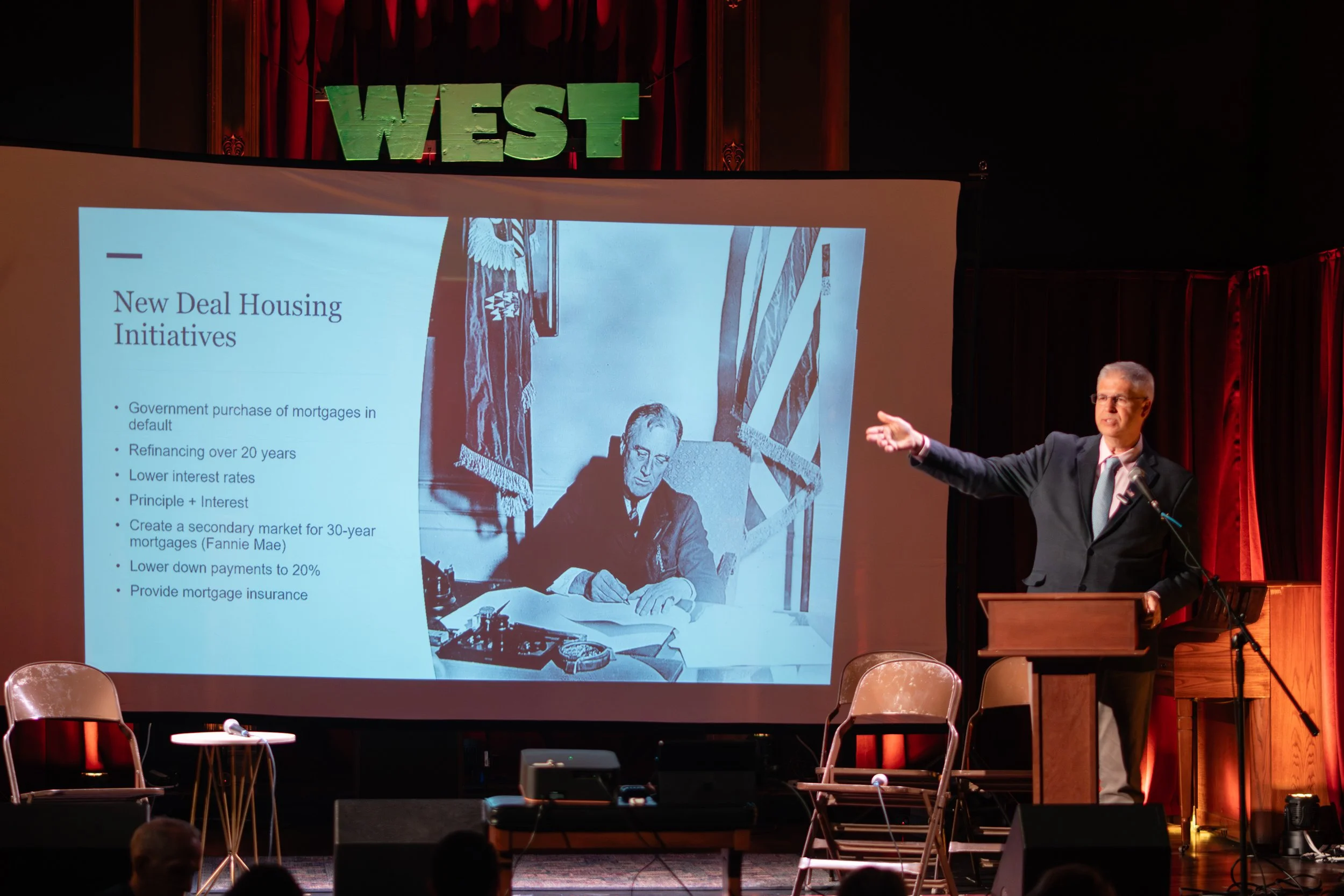

The beginning of the Roosevelt administration was a lot about dealing with this. (And someone told me today I have a spelling mistake on this slide. Which is really weird, because I’ve been using this slide for two years now. I don’t know where it is, but, if you can find it tell me afterward. Everyone’s going to stare at this slide now.) The Roosevelt administration's job number one was to stop this deflationary spiral. Literally, they went out and did a series of initiatives. They went to local banks and said, "Hey, if you're going to foreclose on someone, sell us that loan. We will make good. We will take that loan." And then they would go to the homeowners and say, "Can we refinance that for you, keep you in your home? We'll do it over a longer period of time. We’ll have you make principal and interest."

They wanted local banks to lend more to get more people into homes and have the ability to get into homes. So they said, instead of requiring a 50% down payment, how about you just require 40% or 30%, and we'll create this thing called mortgage insurance, where the federal government will issue an insurance policy to back that loan that you're making. So if it does default, you still are going to be made whole.

The federal government ultimately created a system where banks, if they wrote qualifying mortgages—and I just said that in a way where you're all like, "Oh yeah, that makes sense"—if they wrote qualifying mortgages, mortgages that met very strict, conservative underwriting criteria, the federal government would buy those mortgages if the banks ever needed liquidity. If the bank ever got to a place where, like, “We need cash, we’ve got too many loans,” the federal government would buy those loans from them.

Banks don't like to do longer-term loans for a variety of reasons. The Federal Government said, "We'll give you 12 year, 15 year loans. We will buy those." Ultimately, we created this organization called Fannie Mae. We said, "If you want to write 20 year mortgages, we'll buy those as well." And so the federal government stepped in and backstopped this system and stopped that deflationary spiral, stopped the cycle of people getting foreclosed on and kicked out of their homes and essentially stabilized the housing market during the Great Depression.

I use a word in the book to describe this, and I'm going to use the word here tonight. I think, for many, many reasons, this was a very moral thing for the country to do.

World War II and the Post-War Boom

Now, let me ask you all a question. This is the public participation part of this presentation. I want to demonstrate something to you. You know the answer. The thing that got us out of the Great Depression, we are all taught, was?

(Audience: “World War II.”)

There we go. You know you live in a world dominated by economists and economic thinking when we are taught that the thing that got us out of economic depression, out of hard times, out of extreme difficulty, was a global war. Right? It's like you’re a bean counter at the Treasury Department, at the Federal Reserve, you're like, "Oh, things are so hard. Things are so bad. Wow, yay, global war—we've got our mojo back."

But if you look at the economy in this way, if you don't care about human suffering, you don't care about tens of millions of people dead, you don't care about families ripped apart, you don't care about any of these things—what you care about is GDP growth—World War II is amazing. Because we took all these people who were unemployed or underemployed, and we sent them overseas to kill and to die, and we took a whole bunch of other people and put them to work in factories building things that had no intrinsic value to society but would be used in this conflict—things that we would blow up and throw away, ultimately, at the end of the day. This boosted GDP.

And again, you all said it. I agree with you. We are all taught the thing that got our mojo back out of the depression was this global war where we could spend a ton of money. As the war was winding down, the thing that our economists were freaked out about was that when the war was over we would just slide right back into the depression. When we demobilize these troops, we shut down these industries, we're just going to go right back into the mid-1930s.

Of course, that's not what happened, right? What happened is we built this brand new version of America. We built what we at Strong Towns call the suburban experiment. We started to reshape cities around the idea that they could be machines and engines of growth. That we could pump money into infrastructure, into highways, into commercial real estate, into subsidizing housing, and we could get out of that growth, growth, growth, build a middle class and have a prosperous nation—not slide back into the Great Depression.

Growth as a Policy Priority

What we did, from a housing standpoint, is we took those tools that we used to stop the decline in housing prices, that deflationary spiral, and we repurposed those tools to make the economy go up, to make housing prices go up, to make demand for housing go up.

You had a 50% down payment—how about 40%? How about 30%? How about 20%? How about 10%? How about a 5% down payment? How about no down payment? How about down payment assistance?

You have a 15 year mortgage—how about a 20 year mortgage? How about a 30 year mortgage? 8% interest rates seem too high? How about 6%? How about 4%? How about 3%?

All these things, in a sense, allow people to borrow more money and to spend more on housing. And what we saw at the end of World War II is this insane amount of growth. This is crazy. I said insane. I probably should have said joyous, triumphant amount of growth.

I try to be as understanding as I can. My grandfather grew up in the Great Depression. He lived in a barn during his teenage years, and that sounds very odd, but the family up the street allowed him to sleep in the barn, they fed him, and then he worked the farm. That was the arrangement he had during the 30s—a barn in Minnesota. The lesson I took away from that was that the 1930s were really tough, because my grandpa said he had it very well off compared to other people. That does not seem very well off, but that's what he always said.

So I try to be very understanding of this generation that lived through the Depression, lived through World War II, got done and said, "Alright, let's go." And truly this was a massive success. Allowing people to get into homes in this way, we celebrate today as this massive success. We built a middle class. We allowed people to have this upward mobility. We grew our way out of debt.

The Economic Impact: Explosion of Private Debt

This is the 25 years after World War II. This is what happened to our gross domestic product, the size of our economy. The largest expansion in the country's history came in the two and a half decades after World War II. We did expand the federal debt—that's this line here—but by a very small amount. And what this did is allowed us to grow our way out of that debt we had at the end of World War II. That was our debt-to-GDP ratio. We talk about this today—the Greatest Generation, right? —as this great American success story.

What is often not told in here is the effect of private debt. What we did is we shifted our growth strategy from one of public debt to one of private debt. The private debt market, the mortgage market, took on over 1,000% debt increase in that period of time. Americans took on billions of dollars of private mortgage debt to finance this construction, and it was extremely successful from a macroeconomic standpoint. But as we've talked about for a long time at Strong Towns, there's a lot of lingering aftereffects for our cities, for our communities, for our families in terms of that debt overload.

The Case-Shiller Index

I think we could spend two hours on this chart. I know not everyone likes charts. I'm an engineer, so I'm kind of obsessive about them. This is the Case-Shiller Index. If you've ever listened to economic people talk about housing, they'll often talk about the Case-Shiller Index. This is an index of home prices compared to wages. So if we doubled everybody's salaries tomorrow, housing wouldn't become affordable—housing would just double in price, right? So this tries to even that out over time.

The index runs from 1890 through today. What I've got up here is the end of World War II—1945 on the left, on the right is 2008. What you see in here is a period of time after World War II where there's a little bit of volatility, before you have this long period of declining home prices. That long period of declining home prices is suburbanization, that first generation of suburbanization. We're figuring out supply chains, we're figuring out manufacturing, we're figuring out all this stuff, the same way that the price of big flat screen TVs has gone down. That's what you're seeing from the end, from the beginning of World War II through the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s.

But then you have this inflationary episode, and you actually follow it by another inflationary episode. In both of these episodes, what you saw was the dynamics of the 30-year mortgage starting to weigh on local banks. Local banks borrow money from depositors, and then they lend it out, in this case in the mortgage market. The reason you have three year, four year, five year balloon payments is because if you lend out at, say, 6% and you have an inflationary period and all of a sudden you have to pay depositors 7% or 8% or they leave your bank—if you're lending at 6%, now you're losing money.

If your loans roll over every three, four, five years, there's an end to the bleeding. But if you've been induced by the federal government to take on a 20 year or a 30 year mortgage, there's no end to the bleeding. Your bank is going to go bankrupt.

What we saw at the end of the 1960s is that a whole bunch of banks started to become insolvent and go bankrupt. The federal government stepped in with the first bank bailout. They created an organization called Freddie Mac, they created another called Ginnie Mae. These were specifically designed to buy mortgages from banks. So basically, "This is a bad mortgage. The federal government will buy it and give you cash for it so that you can go lend some more." And it restored prices—they went back down.

We created a second bubble in a second inflationary wave. We hit that interest rate peak. Banks started to fail. Prices collapsed again. We injected more money back into banks. We went through a deregulation cycle that gave us the S&L bubble, and then we went through this decentralization bubble, I think is the best way to describe it, where we loosened up rules, loosened up regulations, tried to standardize and “algorithmic” things like credit scores and assessments and appraisals and insurance and all kinds of other things, and created this massive, massive housing bubble.

Each Bubble Bigger Than the Last

I said we could spend two hours on this. There's so much here. What I want you to walk away from is to recognize the amplitude difference in all of this.

We have this long period where prices are declining because we're creating efficiencies in the market, but then the financial structure of what we built starts to impact prices, and you see an inflationary run-up. You see a second inflationary run-up. You see another bubble with the S&L. You see another bubble with subprime. Each of these bubbles is bigger than the next. The amplitude is bigger than the next.

What you are watching is you are watching housing shift from being a localized product where price is reflective of supply and demand within a localized market, to an international financial product where prices are reflective of capital flows, interest rates and other macroeconomic things.

Where are we at today? We're at the next amplitude of this.

I listen to people talk about, "Oh, land is so expensive. Oh, properties are so expensive. Oh, all this is just crazy. We need to figure it out." It is. We're living through absolute insanity in terms of housing prices.

If you're sitting here going, "This doesn't make sense," you're right. It doesn't make sense. People can't spend 60% of their income on housing. People can't spend the amount of money on housing that we're asking them to spend. But if you look at the way we've financed this stuff, if you look at what we ask people to do, we have really reached a place of total insanity.

The Housing Trap

Here's the housing trap. In the 1980s, when we were going through the ramp-up to or the fallout from the second inflationary bubble, the rescue of the banks and the ramp-up into the subprime or the S&L bubble, one of the things that we did to juice demand for mortgages—which, again, in Finance World, we don't talk about housing, we talk about mortgages—one of the things we did to juice demand for mortgages is we changed the bank rules so that local banks and regional banks and national banks and insurance companies and pension funds and everything else that's regulated by the federal government that has to have reserves on hand can hold as reserves cash, Treasury notes or mortgage-backed securities.

Mortgage-backed securities always pay a higher rate than a short-term Treasury note. They just do. And so what we did is we created an insatiable demand by local banks to buy those type of instruments. Every bank, every pension fund, every insurance policy—all of it is backstopped today by bundles of mortgages that probably all of us are paying on every month.

And so when housing prices go down and those mortgages fail, even a percentage of them fail, it undermines our entire economy. It undermines our entire banking system. You might have heard when we went through the 2008 housing crisis that there's a time bomb in every bank. That is still there, that's not changed at all.

We have an economy where housing prices cannot be allowed to fall or our economy will collapse. And when you recognize that, you recognize the trap that we're in, because housing prices cannot go up, they cannot stay even at the level they're at now, without dramatically impairing our ability to have a functioning society—to get people into housing, to have people go pursue jobs. The American dream. It’s completely impaired by the crisis we have now, but we can't have housing prices go down without destroying our economy. This is the trap.

Political Responses

If you notice in the last election—and I'm going to say some things now, I'm going to ask you for generosity to not look at them as partisan political terms. I'm going to do some analysis that is hopefully party-neutral, but I'm going to look at the Harris campaign and their housing proposal.

If you remember back, housing was a big issue for the Harris campaign, and what their proposals all centered around were things like homeowner assistance, first(time) homebuyer assistance, lower interest rates for different groups that were more vulnerable. The idea was to allow people to pay more for housing. So, you can't afford the housing price, but we can't have the price come down. So what we're going to do as a government is fill in that gap for you, allow you to pay that higher price through some form of assistance.

That's because the Harris campaign recognized we're trapped. We can't make housing broadly affordable or we crash the economy, so what we can do is try to help people who can't afford (to) fill in that gap.

The Trump campaign also had some housing discussion amongst their, whatever you would call—I was gonna say policy papers, but policy tweets. Sorry. I’m not a policy nerd either, so whatever. When we look at those, they were more about making it easier for people to borrow more money. So "We want to privatize Fannie and Freddie." Fannie and Freddie are now government entities. We took them back over in 2007 when they were failing. Why were Fannie and Freddie failing? Because they did risky loans? No, because they took on long-term loans, which are really bad.

The government has set themselves up as the last fool at the table to take on all the bad debt. And when you take on all the bad debt, your entity goes bad. So when things went bad, Fannie and Freddie went bad. The government took them over. "We should privatize them again so they can write"—and if you fill in the blank, they will say "more competitive loans." I think you can just hear the correct terminology: riskier loans to riskier borrowers. That's what they want to do.

And this week, the Trump administration came out and backed the other plank, which had been simmering in financial markets, but this is the first time the president actually uttered it: the idea of a 50-year mortgage. So you thought the 12-year mortgage was great—how about 15? How about 20? How about 30? Hey, guess what? We can take that expensive house, spread those payments over a longer period of time, and thus make it more affordable for people.

Both of these parties' policies acquiesce to the trap that we're in. Housing prices can't come down without destroying the economy. Housing prices are too high for people to afford, and so what we need to do is use that financial alchemy to get people into houses.

Housing as Financial Product

In our market today, these are financial products. We look at them and think of them as shelter—single family homes, duplexes, five-over-one apartment buildings. We look at them as shelter. And for housing advocates, we're trying to get more and more and more built all the time. "Just build more and more and more." Yes, these serve as shelter, but their primary purpose in our macroeconomy today is as the backing of financial products.

We can build as many single family homes as we can mortgage. Those mortgages have immense amounts of liquidity. They can be bundled with other ones, chopped up into securities, sold off, hypothecated, bet against, backstopping all kinds of bets throughout the entire economy.

The same thing with the big apartment buildings. You see these same buildings popping up in market after market after market. That's because they're a great standardized product. They literally can be built at a low price point, at a luxury price point, at anything in between, based on where you're at. You can mix them with other ones, bundle them up, cut them up. You can buy a portfolio of people paying commercial real estate loans on these. These are fantastic financial products.

If you recognize that these are financial products primarily in our economy—that's how they function, that's how their price is set—what you realize very quickly is that almost all of the capital available to housing goes to those two products: single family homes, duplexes, apartment buildings, five-over-ones, big construction projects.

Demand for Starter Homes, but No Capital

We talk in housing circles of the missing middle. And I think that there's a lot of validity to that. There's a lot of really smart planners and architects working on that. The reality is there's not a lot of capital to build that stuff.

If we look on the far end of the spectrum, the wealthy end, wealthy people we understand do not have problems financing their homes. They can build bespoke whatever and they can get financing for it, because they are wealthy.

Where there is tons of demand, an overwhelming amount of demand, but no capital to build, is at the low starter end of the market. There is an insane amount of demand, but there's no money to go out and build stuff at that place. There's no mortgages, there's no 30 year loans, there's no 50 year loans, there's no backing to build.

What do these places look like? More than two-thirds of all households in this country are one and two person households. More than two-thirds of all homes in this country are single family homes. What that means is that you have most households in the country living with extra bedrooms.

It is very common, and it would have been very common 100 years ago, for someone who's living in a house with extra bedrooms who, say, doesn't have the money to fix the roof, doesn't have the money to fix the heater, doesn't have the money to pay for their property taxes that are rising every year, has trouble shoveling the sidewalks, has trouble maintaining the yard or what have you, to do the logical thing that people have done throughout all human history: that is, take one of those spare bedrooms, put in a little kitchenette, put on an exterior door, and rent that out.

You can't do that in most places in this country. That's now a duplex. You've got to go through all kinds of regulations, genuflect in front of planning boards, beg permission from your neighbors, try to get variances to do something that is ridiculously simple.

Backyard Cottages and Starter Homes

The same thing goes with backyard cottages. And I know that in jargony way, we call these “ADUs," and ADU sounds like a disease. Please stop calling them ADUs. Normal humans, when we want to be empathetic to people, we have to actually talk in their language.

A backyard cottage is a place where my mother-in-law, who we don't want to put into a home, can live with dignity. It's a place where a college student can live and help out with chores around the place in exchange for rent. A backyard cottage is a place where someone who's recovering from an addiction or a bad marriage or what have you can go and get a start. It's a place where a young family can start out. These are human stories that get lost in our jargon around ADUs and conformance and setbacks and what have you.

These are very, very normal things that people around the world, throughout human history, have done. "I've got extra space in my backyard. I could use some extra money. Let's convert my garage into a unit and rent that out." We put all kinds of restrictions on doing this. Why? Why?

How many people in this room would like to live in a 400 square foot house? How many people in this room have lived in a 400 square foot unit at some point in their life? Look at that. Most people have this starter experience at some point. But what we have done in our economy, in our housing market, is we've made that bottom rung so difficult to get into, that the people who can actually reach it are stressed financially, and the people who can't are put in this financial purgatory where they have to pay ever-elevating rents and can never really save up enough money to reach that starter level.

This is a unique situation to us. Throughout all of history, people have been able to get into—not tiny homes. Tiny homes are like a weird fetish thing that we do. They get into starter homes, which is a 400, 500, 600 square foot home. It's a small house. If you go around your neighborhoods here, you will see tiny homes that were built 100+ years ago. They're no longer tiny homes, because what happens when you move into a starter house? You save up a little bit of money and you do an addition. You have a kid, and you put on a second story. The house continues to grow and expand.

You get into what you can afford today. If you're going to have a starter house, it's a 1,400 square foot home with a huge mortgage. All of our ancestors would have built a 500 square foot home, and over time, as they could afford it, built it to be 1,400 square feet. We can get people into smaller houses. We can get people into decent places for them, and we can do it at much, much lower prices.

Three Things That Need to Be Done

At Strong Towns, we talk about three things that need to be done to get us into a different housing paradigm, one where we are filling that market of entry-level units.

We need code reform. We need to change our ordinances, our regulations, to make this stuff easy to do.

We need to create an ecosystem of incremental developers—people who are going to go out and build this stuff, because they're all over in our community, they're just on the sidelines. It's not the builders we have today. They're building profitable stuff in other places. What we need is a new version of developer, the person who looks at it as a side project that they can grow into.

And then we need to be able to finance these units locally. We actually need local governments to be the investor making these projects happen, not as a way to do charity or to lose money, or to take a little bit of the budget and throw it away on some housing initiative that doesn't scale, but to do it without losing money and without taking risk, so we can do as many units as our community needs.

We have created two toolkits, and we're creating the third to deal with each of these. If you go to strongtowns.org/housing-ready, you're going to get the first two toolkits.

Regulatory Reform and Building an Ecosystem

The first one is about regulatory reform. Here's the reforms that we need to make in our city to make this easier to do. There's always people who have other suggestions or other things they think should be done. Yes, do those too, but here's the six kind of universal ones to get us started, to kind of whet our chops on doing reform.

The second toolkit is about that ecosystem. It's about shifting the culture at City Hall, the culture within our community, to actually grow an ecosystem of developers. And let me, just as an aside, give a tiny little vignette of what I'm talking about.

In South Bend, Indiana, they started holding these developer conferences or meetings. I don't even know what they call them. It was basically, they got a room, one night a month, they would order half a dozen pizzas. They would have a bunch of pop, and they would invite anyone who was interested in doing development on a neighborhood level to come in, and they would just chat. They would sometimes have a speaker who would get up and talk about how to finance a house at a bank, or how to get a permit from the city or what have you. But really what they were doing is they were getting people together.

Because the thing about incremental developers is that they're not competitors. These are people who are like a teacher who wants a gig in the summer, or someone who has a house that's kind of run down up the street that wants to buy it and fix it up and sell it, or someone who's pounding nails for someone else who wants to do a side project. Once you get these people together and talking, what happens is they start solving each other's problems. "Well, you're having trouble getting a loan? You should go to my bank. My banker over here, he's really great. Oh, you had trouble with a plumber or a carpet layer? I know one that's really wonderful."

And the thing is, all of those kind of sub-industries are contracting with the big builders, but they love, love, love working with the incremental developers. And so once you get a good plumber who knows how to do it, they start referring everyone to them. And that plumber can leave their job as a plumber doing projects on the side, and go do it full time. You can start building up all these industries.

And if you look in South Bend, they've been doing this long enough, and they have an entire ecosystem of not just people out building, but people supporting those builders out doing that, from bankers to subcontractors all along the way, and they're getting cheaper homes at scale as a result.

Local Alternatives to Conventional Financing

The third toolkit, which is going to come out at some point in the early part of next year, is going to be all about finance. How do we finance these units at scale without the city taking on risk, without the city going broke, without the city losing money, so that we can finance as many of them as people can build in our community?

There's lots of cities doing this in unique ways, ways that do not put the city at risk. I got a little feisty today at our thing this morning that I did at Villanova, because I really am allergic to the idea that local governments can be flippant about their budgets and just lose money randomly. Every local government you see will have this thing like, "Oh, we need 10,000 new units." And they're like, "Okay, well, let's move heaven and earth and do all this stuff and undercut our budget here and throw money at that. And how many units will that get us?" "200." "All right, let's do it."

It doesn't scale. It doesn't work. We actually have to attack this problem more strategically, and that means that local governments can be the difference maker, but they can only be the difference maker if they don't go broke, if they don't lose money, if they're not the dumb money at the card table.

Retaking Control

This is the book. I tried to cram that all into 30 minutes, and it's 37, so I went a little over time. But let me just say this as an ending: I think the thing about the housing crisis that gets to us is that we all feel a little bit disempowered, like the problem is way bigger than what we are able to handle. And if we stay stuck in the current paradigm, where we're literally trying to build houses within the current system, we will always be frustrated, because the current system is all about maintaining high prices.

The only way we break out of this housing trap, the only way we regain our agency, the only way we actually deal with this problem is to actually step back and recognize that the market we can affect is that market for entry-level units. And if we get dedicated to filling that market, not only can we build enough housing for people who are trying to get in at that entry level, but we'll take the pressure off all the rest of the market. And so when people do enter that market, they can enter it from a position of strength, not of desperation. And that will make housing prices locally better for everyone as well as getting people into houses, which again, I’ll use the word, is a very moral thing to do.

Thank you for being here tonight.

Samantha Gray –

Panel Introduction

So each of our panelists works every day at different parts of this puzzle, from development and planning to nonprofit housing and community partnerships. Our goal over this next bit is to connect some of what we just heard to what is happening here on the ground, what's already working, where we're getting stuck, and what it would take to move faster and smarter together.

First, I'd like to welcome Mr. Ethan Demme. Ethan serves as the chairman of East Lampeter Township Board of Supervisors, and is the CEO of Demme Learning, an education publishing company based in Lancaster. He's passionate about helping families build lifelong learners and creating neighborhoods that work for real people.

Next, I'd like to call up Dana Hanchin. Dana is the president and CEO of HDC MidAtlantic, a nonprofit that creates, preserves and manages affordable housing across Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland. With three decades of experience in community development and housing, Dana's organization provides homes for over 4,500 residents and is deeply committed to building opportunities through stable, affordable housing.

Next, Ben Lesher. Ben is the president and founder of Parcel B Development Company, a real estate development firm that focuses on multifamily and urban redevelopment projects in south central Pennsylvania. For more than a decade, Ben has honed his skill and vision for development through a wide range of experiences, from local adaptive reuse projects to feasibility studies and development consulting services across North Carolina.

Chad Martin. Chad brings over 25 years of experience to the nonprofit sector in his role as the first executive director of Chestnut Housing. In addition to executive leadership roles and board service for a variety of organizations, he's been a pastor and art teacher and the director of a multimillion-dollar grant program to support the preservation of historic church buildings.

And then our final panelist, Douglas Smith. Douglas is the director of location and land use at the US Green Building Council, where he leads national strategy on sustainable planning and development. A former bureau chief of planning for the city of Lancaster, Douglas brings deep local experience in zoning, land use and urban design.

I'm here to provide facilitation, but I think this group can handle themselves pretty well. We're going to try to get through each of the panelists—each has a question. We had some overlap, but I was wondering if we could start with Ethan. I know that you've been talking a lot about how zoning rules affect what kinds of homes can exist, especially the smaller, more flexible options that used to be common in Lancaster. So I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit more about that and get us started.

Panel Discussion

Ethan Demme: Thank you. So I've talked a lot about accessory dwelling units, backyard cottages—I've got to correct the language. So we've talked a lot about ADUs, but I want to shift a little bit historically. Another way that people made money off their own assets in the past was boarding houses. You rented out a room. We call that, using fancy words, "SRO," or single room occupancy.

We still have them. They're usually just in the gray area of zoning where it's a flophouse, or people doing it until they get caught, often operating in unsafe conditions. Or we have recovery houses, which is you go through the state, you have a recovery house—it's a boarding house, but you have to be an addict to get in, and those function as boarding houses. How would you recommend townships get back to just allowing boarding houses to exist legally?

Chuck Marohn: You're asking me ... I mean, yes, make them legal. it's interesting, and I feel like—the thing that I'm interested in here, personally, is that you all are dealing with this on the ground. I'm about 15 years, 13 years from the last permit I ever wrote, the last council meeting I ever attended as an administrator. So I think your experiences are fresher.

But to me, the whole … there's a lot of people who are talking about abolishing zoning. I feel like I'm empathetic or sympathetic to that desire. I think there's got to be a methadone, in a sense, kind of transition, because I don't think you can just culturally ban it or get rid of it and then have things work out the way you hope they would. But that's one instance where I think you could, right?

Why are we regulating that aspect of it? I think from a health, safety and welfare standpoint, a flophouse, you should probably have some regulation, but it would be regulation like you would have with a hotel, not regulations like you would have with building a house, right? That's a different kind of regulatory regime that you're looking at different things. You're not as concerned with how many units per acre do you have, but you're concerned with: Is there proper sanitation? Is there a proper bathroom? Are you changing the sheets? That’s a different thing than what you or I would do with trying to get a housing unit available. You see what I'm saying?

Ethan Demme: Yeah, so on the boarding house piece, and this is one of —in East Lampeter we actually do have the ability to do accessory apartments and dwelling units detached or attached by right in any zoning district that you allow housing. The piece I’ve looked at when I look at other areas — the boarding houses, I call it “the next layer down,” where you really have that real entry-level low price point piece.

And functionally, our cheap hotels are boarding houses. The problem with most of what I call the illegal housing that goes on—whether it's illegal flophouses or hotels—is if you complain because the door gets locked, your emergency exit is locked every night with a chain, you get kicked out. You have no tenants' rights, and it's one where usually the property owner has an incentive to keep it illegal and do it, and the township has an incentive to also keep it illegal and allow it, because if it gets bad enough, you just shut down the hotel, kick everyone out, or we've got to remodel the hotel and kick out everyone.

So it's one where the incentives aren't aligned. And to allow local government or local business to say we want to actually make this legal housing, which is what everyone currently is doing—so the incentive structure is the problem that I find. In my township and other townships, we're kind of okay with people living in the gray area, because if it gets bad we can kick them all out, but it's not good for the people who live there.

Chuck Marohn: Yeah. I feel like, I mean, there's a parallel here in the lending markets, and this is often the case for payday loans and some of those things that we see that are very exploitive. People who are desperate for money—and there's an argument on both sides of this—that they're exploited, but also they provide a function, because the next level down is a mafia loan, where if you don't pay it, they break your kneecaps. You know, at least those are regulated.

I feel like you're kind of making a similar argument where, "Okay, we're going to just pretend this isn't here because it serves a function, but because we pretend it's not there and it serves a function, it actually does it in a way that is often not to the standard." If we acknowledged it and nurtured it, you could provide it at the same price, basically. I think that's a good, it’s a great insight.

Ben Lesher: Just to build on that. So I'm really interested in shared living, boarding, rooming houses. There's even a project proposed locally here in the city that did that. The developer had looked at it—they had trouble getting financing for that. I looked at its issues. There's no comps in Lancaster for that kind of thing. It doesn't fit well into the boxes.

So I think that's one of my questions overall. As a small developer—meaning it's just me doing projects—I've been fortunate enough to have access to enough capital to do large projects, but I always feel this push to go big for a lot of things we talked about, and I feel often like that's the only way to go. So I'm just interested to hear, how do we actually get that capital for these smaller developers to actually do small projects?

Chuck Marohn: I'll give one quick example. This is turning into a question for me, we should continue this panel, but let me try to fill in that gap just a little bit.

There's a city down in Florida—I always forget the name, so I'm not going to try to pretend to know—but: Cities have millions of dollars of capital that they have flowing through them every year. All the taxes that are paid come in. They pay salaries and what have you, it comes out the door for the city. It might be $5 million, might be $10 million, it might be $50 million, it might be hundreds of millions of dollars that they have.

Banks struggle to write products, to write loans on products where there isn't a secondary market. They'll write you an insane seven-year auto loan, because they know that if they need cash someday for whatever reason—like, you know, a couple loans in our portfolio went bad, we have to increase our cash reserves—well, they can always do that by selling one of these standard products onto a secondary market. There's a secondary market for seven-year auto loans. Just check boxes. As long as you check those boxes, people will buy it. You can reliquefy.

There's no secondary market for a boarding house. There just isn't. And so when you come in with this, "Hey, here's the product I want. I want to have commercial on the bottom and residential on top," or "I want to have multiple people living in dormitory stuff," it's like, "Okay, that's really cute, and I like it. You're gonna have to have massive amounts of equity, massive amounts of money down, and we as a bank are gonna have to charge you higher rates, because we know that we have to hold this loan through its entire term. There's no other way to do it."

Here's where cities having capital can make a difference. I think cities have the ability to go—and we've seen them do this—go to local banks and say, "This is the kind of product we want to see. And if you will write loans for that product, we will bank at your bank. So we will provide you with millions of dollars of liquidity. And we promise we will keep it there. Obviously we're going to make payroll, some money's going to come in and out. We're not going to just have it sitting on deposit, but if we bank with you, you will have a lot more resources than you have today, and if you'll write these loans, we'll do that."

This is one way for the city to turn, essentially, their position in the marketplace into the types of outcomes that they're trying to get without having to get in the banking business, without having to write the loans themselves, without any of that.

Dana Hanchin: I'm just going to play off, I think, something made in the earlier session (at Villanova), which I attended as well. I think a lot about that financing, and it has to be your community bank and local. You can't go regional or national or multinational. No, not at all.

I mean, we come into that all the time. We have a product at HDC—and I say that in a very technical term, but we are a nonprofit dedicated to building affordable rental housing, and we primarily do that through the low-income housing tax credit program, which is an indirect federal subsidy to incentivize the private market to participate in affordable housing, because otherwise they won't, because it's not profitable.

In any case, we have a product where we're actually converting some of those affordable units into homeownership, and we've had a really hard time getting banks to finance people who want to buy those homes and townhomes, because they can't sell it on the secondary market. Now, the only traction we're able to have is with community banks. And when I say community banks, I mean like two of them, and we've talked to dozens and dozens.

Chuck Marohn: Yeah, but you don't walk in with millions of dollars that you can park there. That's the difference between what a local government can do.

Dana Hanchin: I can. I mean, we’ve been around for 50 years. We have a good balance sheet.

Samantha Gray: Thank you. Do you have another question?

Dana Hanchin: I do have a question because, you know, on the stage, I just want to fully disclose, HDC is not an incremental developer, right? In terms of what you're proposing in Strong Towns. And so I have a question, or my thought is always about it's not just this thing. It's the "and." It's not just looking at incremental development, but how can we also do that with the larger scale development.

And larger scale in the state of Pennsylvania, roughly, when you're looking at affordable rental housing, is a 60-unit apartment building. It's not that big. We're sort of beholden to the state and the requirements. Even around the corner, we built on a third of an acre, 64 units. It's an infill. It ties into the neighborhood. We used a lot of resources and a lot of subsidy. So I'm curious about your thoughts around that scale of development, that financing mechanism to also advance affordable housing.

Chuck Marohn: No, no, no, it's really good.

Chad Martin: We were told you had all the answers! (Audience laughs)

Chuck Marohn: You heard me today at the end struggle with — I want to be nice, and I don't want to say things that will hurt people's feelings. So I don't—listen, I think if anyone is out there building units, it's a good thing. And I don't have—I have lots of love for builders who are out trying to make things happen. I think that there's a lot of heroic things that people are doing to try to build affordable units, using federal government programs, state programs, piecing together all kinds of things.

I think the thing that frustrates me is twofold, and it's why I don't spend any time berating or belittling or discounting those efforts, but I also don't spend a lot of time cheerleading them.

There's two reasons. The first is, I don't think that we should have to be heroic to do normal, decent things. I think when you have a society where you have to have this heroic effort, where you're this astounding person who can get money here, get money here, get some duct tape and baling twine, put this together, and then maybe at the end of the day, you get 60 units—I feel like we're wasting the human capital of people who are astounding doing things that should be much easier.

The second thing is that I look at those efforts that are heroic, and I recognize that on their own, they don't scale. They will never scale to the size of the problem. And they're actually caught within the trap, just like everybody else.

And so for me, I feel like those efforts don't do any harm—like, there's nothing bad coming out of them. And if we do the stuff that we talk about at Strong Towns, the incremental development, the bottom-up stuff, that we will just make, hopefully, it needing less heroism to make those things happen, so that more people then can ultimately do that.

And so I'm—I think if I was being unkind, I would say, I wish you didn't have to spend so much of your time and energy doing that. I would love to see your life used in a way that was able to produce more. It's frustrating to me that you bang your head against the wall to get a number of units that are meaningful to people but not meaningful in the macro sense that it's actually solving the broader problem. Is that fair?

Dana Hanchin: So that’s 30 years of my life. Thanks, Chuck. (Audience laughs)

Chad Martin: Chuck, I have another question for you about—we were told to bring questions—we can all chip in on this one. I have another question that we can definitely all chip in on as we’re sitting up here. But I have a very specific question about incremental development, because I'm kind of with you, that I think there's a ton of opportunity to engage folks in projects that they conceptualize that are achievable. Or, how do you train folks up to do something just to step beyond what they thought might have been achievable for themselves, not the impossible thing?

What I'm curious about is, at least what I saw in the South Bend example you outlined in your book, is such hyper-local focus, that we're talking about a house at a time, a rehabilitation at a time. I'm curious if you have specific examples around incremental development hitting that next scale up in that kind of missing-middle range where folks are not figuring out 18 funding sources to build 60 apartments, but maybe they figured out a neighborhood way to build a quadplex together, or a mid-rise with 10 apartments together. And what does that look like?

Chuck Marohn: Yeah, it's a really, really good question. There's a dude in South Bend, actually, I’m glad you brought it up. His name is David Matthews. Don't call him Dave Matthews. (Audience laughs) Same name as Dave Matthews. And he started out as the hacker, like, "I'm going to fix this up. I'm going to do this." The last time I was there, he was building row houses, like multiple units. And it was in a sense, he graduated out.

And by graduating out, I'm surmising a little bit, because I talked to him about his business model and what have you. I don't know exactly what his financing was, but I do know that at a certain level he had multiple things going on at once. And there's a certain—I've seen this with other developers, and I got this impression from him, too. When you sell this one, you can take the profit, or you can roll it over, and when you roll it over, it has tax advantages. And so in a sense, when you aggregate a bunch of—when you start to do this at a certain scale, you actually can self-fund the equity, where the capital access becomes a lot easier. And so I do think there is a way you get to missing middle through that.

I watched him do it. There was a group in Akron, Ohio, that I also watched do it. They were doing very neighborhood-level stuff. This was a nonprofit housing thing in Akron. I can't remember the name of that group, but they were doing neighborhood-level stuff, and in a sense, built their internal capital flow up to where they could take on bigger projects. But they were doing it because they could walk into the bank with 50% equity starting out, so they were not having to ask for as much financing as they would have if they were trying to piece this all together. Does that make sense?

Chad Martin: Yeah, totally. I mean, we're sort of doing this at Chestnut Housing, but as a nonprofit, and our solution to financing is donations, which is not scalable.

Chuck Marohn: It's not scalable, but it's actually a decent way to get started. And particularly, I mean, I don't know if you're asking people for money as a donation, or if you're asking people for money as investors, but you can go both ways. And the investment money, you know, a lot of times I've seen this with churches that have started to build housing. Actually they’ll go to their parishioners and say, "Hey, we asked you to donate for this thing, but now we're not asking for you to donate, we're asking for you to invest, and you will get your money back, maybe with some interest, but maybe not, but you will be the first one cashed out in this. But it might take a while. Would you be willing to be patient capital because of this greater social mission?"

And for people with money, they're often willing to do that. They're, in a sense, foregoing the gain that they could get someplace else for a more charitable purpose.

Chad Martin: We've totally found some success with that. And I feel like in this county, where there is a considerable amount of wealth, just sort of tucked around every corner, there's such an opportunity for more of that.

Chuck Marohn: What's the name of your thing?

Chad Martin: Chestnut Housing.

Chuck Marohn: So Chestnut Housing. (To the audience) If you've got tons of money … (Audience laughs)

Chad Martin: There are two nonprofits at the table, we will divvy it up equally.

Douglas Smith: Hi everyone. I have to say I’ve approved projects or helped approve projects for three people on stage, and I find it to be a real honor that I was invited to talk about efficiency in government and approving housing units, so thank you for the invitation.

So in my time at the city of Lancaster, I was chief planner. I reviewed a lot of development plans, and the smaller the project, the more disproportionate the burden was in terms of regulation, usually. And that to me just seems like a major problem, and I appreciate all the streamlining and many of the strategies that you noted.

I'm really curious about pre-approved building plans, and also to go sort of a step lower, like modular building plan approvals, where we're actually approving systems like a foundation. And then, to Chad's question, maybe, are there ways that we can actually stack that so that that can actually become the three-unit or four-unit?

I know South Bend has experimented with these a bit, but I was hoping you could just talk about some of your experience. Are there pitfalls there? From the Lancaster experience, I think about exterior building and historical approvals, which are a big deal here, and that may be providing some sort of streamlined way for the historical board to also be approving some housing that is appropriate for the city, architecturally and preserving the character, but also really trying to get to the streamlining. So I'll leave it at that.

Chuck Marohn: I feel like the pre-approval plans are one of these obvious things that once you see them, or once you interact with them, it's like, "Oh, that works." You're basically just saying, if you build this, we've already reviewed it, it's good to go. And so you let the developers pluck things off the shelves. Could you scale that up to a three-unit or four-unit pre-approval? I don't see why you couldn't. You're just architecturally talking about more work, right?

Where I've seen the pre-approved building plans work really well is with the starter homes, the backyard cottages, that kind of thing, because they are really simple, and you can have 16 of them and come in and pick the one that you want.

I feel like, to me, the thing that I've seen, and it was Rebecca Kik who did this, who's in Kalamazoo, she was in your position, and basically wanted to have a dialog about how we speed up the permitting process. And so what she did is she went to the planning commission and said, "Here's something that you all said you wanted." She did this on multiple things, but let's say it's a backyard cottage. "Here's a backyard cottage. We all want this to happen, right?" "Yeah." "Okay, I'm going to submit a permit to our department for this backyard cottage on this lot, and then we're just going to follow it through the process."

And so 60 days later, it got approved, it got through the process, and they had basically noted where it was during this entire time. And the thing that they found is it spent 42 or 43 days on the fire chief's desk.

The fire chief is a really busy person. So the question was, "Why on the fire chief's desk?" And they actually went and talked to the fire chief, and the fire chief said, "Well, what do I look at? I look to make sure there's 10 feet of separation between where they're putting it and every other building." "Okay, so if we can just say there's 10 feet of separation, does it need to go to you?" "No, it's a pain in my ass. These just sit here, they back up until I’ve got 10 of them, and then I review them, and then they go out the door."

So what they realized is that they could, for those specific applications that were simple, where you had the—they also did a lot of pre-approved building plans in Kalamazoo where they had these things—that they could shrink the permit approval process down to literally one day. They can approve it the next day. Because what they did is they said, "All right, if you can meet all these things, we can skip review point A, B, C and D. Or if you need an on-site inspection, we'll actually schedule that out. So we'll come out and look at the thing before you even submit your application. So we all know it's going to be approved walking in the door."

I don't think you can do that for Costco or the big apartment building or the new subdivision on the edge, nor should you try. But we certainly can do it for this layer of units, where we're trying to give the builders more confidence that when they walk in the door, we're on their side, and we're gonna get that thing approved. So long as it meets the code, too, right?. We're not talking about bending codes or changing things, we're just talking about our internal process.

Douglas Smith: I think that makes a ton of sense. There's often unique site conditions around the building that, of course, have to be taken into account too. So I kind of see that building approval, or pre-approval or whatever, for a streamlined permit being one thing, but then you have to put it into the site and get that to work, too. Stormwater is another big deal here in my experience. But I think about a similar sort of off-the-shelf permitting process. A project that has 500 square feet impervious, a project that has 1,000, or 5,000—actually having pre-designed stormwater solutions for that. So I think you can take that idea in a lot of directions.

Chuck Marohn: There's an interesting thing, though, and you said stormwater is an issue. It made me think of wetland regulations. You know, for wetland regulations in general, if you are affecting a huge area, there's a big lumpy process you have to go through. But if you're impacting a small area, there's actually a lot of local discretion where you can say, "Okay, we're impacting this, but we're gonna expand that. We're gonna offset that, or put money into a bank, or what have you."

I feel like often what we do, and I'm interested in your take on this, is we treat the analogy would be treating the small 100 square foot wetland intrusion like the 10-acre wetland intrusion. We kind of have the same process with the same thought, with the same sensitivity.

And the reality is, if we screwed up a backyard cottage or a small house, Okay, a starter house, that wouldn't be great. But it's not the end of the world. We could probably figure that one out. If we screw up a 100-unit subdivision, or the massive apartment complex, or the next Costco or whatever, yeah, that's going to be a big deal.

I almost feel like we have to develop a culture of, "We will have our hypersensitivity where it matters most, and have lower levels of sensitivity," which means a trade-off. Like, there will be some small mistakes, but they'll be mistakes we can live with. Does that—I feel like that's a hard culture shift. (Audience applauds)

Douglas Smith: I totally agree with that.

Charles Marohn: Here's the thing, everybody who clapped: the next time there's a small issue, and people are at the meeting yelling at the City Council, and then the City Council adds 10 pages of regulation to the code, "This will never, ever happen again on our watch," I want you to be there to push back on it and say, "No, sometimes things happen and we shouldn't overreact." That's the trade-off.

Douglas Smith: I totally agree. I’ll add one point and then I’ll pass the mic. To that point about not overreacting about small incursions, I think also recognizing the immense co-benefits that incremental development brings as well is something we need to talk about as well. It's not just accepting minimal harms, but it's actually accepting, I think, a huge number of co-benefits. The trade-off is huge.

And I'll leave a thought maybe for the group: housing has been the source of a lot of problems, right? We put housing in the wrong place, now we have transportation issues. So I think it would behoove all of us, as we’re taking maybe some guardrails off here to encourage development, to be thinking about: what are the co-benefits we can be designing for? How can we really juice this to make sure it is everything that it needs to be in this moment of so many complex overlapping problems? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Samantha Gray: If everyone could give their one last thought.

Ethan Demme: I think the bigger discussion that I see here is what you're really talking about is democratizing financial access and bringing labor and capital together at local scale, whereas the large businesses, the large capital structures, even the large labor unions, all work well to do the big, normal-sized development. The local development is, "Hey, we have local labor, accessing local capital to create local financial prosperity."

We're actually creating a dynamic capitalism, where I would quote G.K. Chesterton: “The problem with capitalism is there's not enough capitalists.” We're making the local family who has a home equity line of credit of $100,000 be able to say, "I can put a backyard cottage in. I have my own capital, because I've got a $300,000 house that I've paid off for 20 years." So, educating people that they can use that is one of—We have enough space in Lancaster County to solve the housing problem on existing lots of existing homes, and we've got enough builders. Two Amish guys and a weekend. But this is about reframing it as: The government needs to get out of the way and allow people to actually make money with their own asset and not restrict it and say, “You're not allowed to make money with your asset, only the big guys are allowed to do that.”

Dana Hanchin: I guess I also want to just add the human element of it, because you have to then educate and inform and have people want to be able to do this, right? If they’re not interested …

Chuck Marohn: Here's how I would—you used some buzzwords that, you know, capitalism and what have you that I try to avoid, because it means different things to different people. Here's how I would say it slightly differently, but I think agreeing with you 100%.

In the 1930s the federal government stepped in to address a gap in the marketplace where people were losing their homes and people were being treated poorly. The federal government stepped in and created a market that didn't otherwise exist for long-term mortgages, long-term. Now I'm not happy with that market. I don't like it, but it exists, and we all live with it.

Right now, there is an absence of a market at the local level for entry-level units. The federal government is not going to step in and fill that gap. The state government might, but really has not the right structure. The people who can step in right now, today, is local government. And when I say local government, I don't mean the algae in the food chain of governance, like the lowest level of government. What I mean is the highest level of coordination for us in a community.

We actually can step in, in cooperation with local community banks, local philanthropists and others, and fill that capital gap and create a market where there's enormous demand today, but our macro system is not filling it.

And so I do think that that is, in a sense, applying capital to where capital is needed. That's what a functioning market does. Our market is broken in that part, and we can actually fill that part in and make our competitive market more complete.

Samantha Gray: Final comments?

Ben Lesher: Oh man, what do I say? I like these ideas—incremental development, creating smaller developers. I think I still, in my mind, have this question of, this is just a massive problem. I think the flyer said in Lancaster County, 18,500 new units. And, I'll just say it costs at least $350,000 per unit. I think that's $6.5 billion. That's a lot of money. And I just, you know, I like small, many small projects. But is that going to get us where we need to go? I want to end on a more hopeful thought than that, but that’s where I’m at right now.

Chuck Marohn: Watch the movie Dunkirk.I really do think that there's an aspect of this—and I get, one of the questions I get all the time, or one of the pushbacks I get all the time is "Chuck, the problem is so huge, we can't do incremental." And I think what is not recognized fully—not that you said this, but I'm adding on—is that the bigger you are, the harder it is to be adaptable, the harder it is to move in these smaller increments.

And what we see is that our market for housing is actually kind of stalled out, stagnant. It works and it functions, but it doesn't work in the way that I think if it were responsive to supply and demand at the local level, you would see. A lot of people blame just regulation for that. I think that is more about capital than about regulation, although there's a mix of both in there.

The Dunkirk example, for those of you—at the beginning of —why do I want to say World War I?! — World War II, the British got backed up, got pushed by the Germans up at Dunkirk. And as they were trying to evacuate, the Germans were just destroying every big ship that came to pick them up. And the way they solved the problem is by sending thousands of little ships to pick everybody up. And they were able to evacuate the troops and save the British military.

I do think that small does not work in isolation, but when you do it and you do it—and you know, South Bend is a really good example of this—you do it over time, it starts to compound on itself, and you do get compounding returns from it in a way that does scale impressively.

So I get the urgency of the moment. I would not allow the urgency of the moment to limit our toolbox to just the couple of big things we can do, and I would invest in this scaling strategy. Exponential growth is an astounding thing.

Samantha Gray: Final thoughts from our panel? (Panel remains quiet.)

OK. I know that I said there would be some audience Q&A, but I want to be respectful of everyone's time. So it is 7:30, so we want to just make sure we say our final thank yous. I'm going to invite Nick Dennis up to say some final thank yous. Please stay around. Our panelists, I don't know how long they're going to hang out, but you can also all talk to each other and share your thoughts and questions at the tables. There's still some food left in the back. Please take advantage of that. And also remember that there is a cash bar. Sometimes conversations are better with a drink.

Nick Dennis (Strong Towns Lancaster) – Closing Remarks

I’m Nick Dennis, the leader of our local Strong Towns group here in Lancaster, and I just wanted to first, thank Chuck so much for coming over. After a full day—you were at Villanova earlier today—you came to Lancaster. So there's something from local Strong Towns.

Chuck Marohn: You're the hero. Here's—we're looking at someone who's doing heroic things. We should be thanking you. Thank you!

Nick Dennis: No, thank you. So just a few things to wrap up. There are surveys on all of your tables. If you want to fill that out, we're hoping to do more events like this. Chuck won't be able to join us —